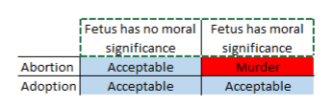

Summary: Human Capital Contracts would allow people sell a certain % of their future income in return for upfront cash, as opposed to taking out a loan. This would be less risky for them, would give them valuable information about different college majors, and would help give people de facto ‘mentors’, among other advantages. Adverse selection could reduce the benefits, and reducing inter-state competition poses a major possible disadvantage. We also discuss two niche applications: parents and divorce.

Debt vs equity financing

There are two methods of financing for companies; debt and equity.

Debt is fundamentally very simple. I give the company $100 now; it promises to give me $105 in a year’s time. They owe me a fixed amount in return. Hopefully in the meantime the company has invested that $100 in a project or piece of equipment that produces more than $105; if so they made a profit on the transaction as a whole. Here the risk is borne by the company; they have no choice but to pay me back, even if they didn’t make a profit this year. This form of financing is familiar to most people, as they personally use savings accounts, credit cards, mortgages, auto loans and so on.

Equity, unlike debt, does not represent a fixed level of obligation. Instead the company owes you a certain fraction of future profits. If you give a company $100 in return for a 10% share, and they made a $50 profit, your share of the profit is $5. Hopefully they will make growing profits for many years, in which case your portion will grow to $6, to $7, and so on. Here the risk is borne by you; if they don’t make a profit, you get nothing. This form of financing is much less familiar to most people; about the only experience they are likely to have would be investing in the stock market, but that is now highly abstract so the underlying mechanics are obscured.

Equity: Less Risky than Debt

One of the biggest advantages of this system is it moves the risk from the individual borrower to the investor. When you borrow money, you put yourself at substantial risk. What if you struggle to find a good job after college? You’re still obliged to make repayments, which could be very difficult if you only have to accept a very low-paying job. Or if you borrow money after college, what if you lose your job? Or have a family emergency? Your circumstances have deteriorated, but you’re still obliged to make the same level of payments – meaning your post-debt income falls by even more than your pre-debt income.

With equity, on the other hand, you don’t have the risk. If you don’t find a job after college, your income will be zero, so your repayments will be X% of 0 – namely 0. If you find a low-paying job, your repayments will be low. The investors will be made whole by the people who instead find high-paying jobs – who can also afford to repay more. So equity investments better match up your repayment obligations with your ability to repay.

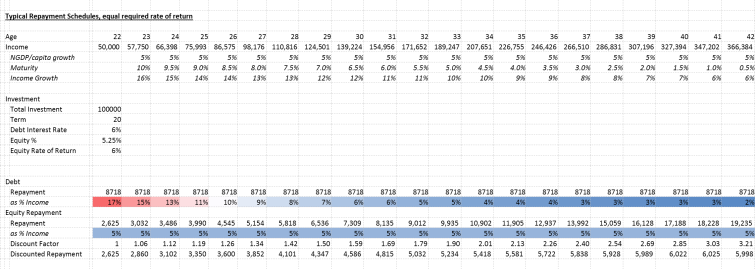

Here is an chart showing the difference, in terms of the % of income you’d be spending on repayment, from an example worked out later in the article:

The risk is transferred to the investor, who now loses out if you don’t have much income. But they are in a much better position to deal with the risk – they can diversify, investing in many different people, and also in other asset classes. Some human capital contracts could be a good diversifying addition to a conventional portfolio of stocks and bonds.

Education

Funding higher education is perhaps the best application for Human Capital Contracts.

Firstly, this is an extremely risky investment. There are countless stories of people who took out huge student loans to fund an arts degree and then have their lives dominated by the struggle to repay. Alternatively, if people could discharge education debts through bankruptcy, the risk to the lender would be too great, as the borrowers typically lack collateral, so loans would be available only at prohibitively high interest rates, if at all. Selling equity shares would avoid this problem; people who did badly after school would only have to repay a minimal amount, but lenders could afford to offer relatively generous terms because the average would be pulled up by the occasional very successful student.

The other appeal is the information such a market would provide students. It is fair to say that many students don’t really understand the long-term consequences of their choices. The information available on the future paths opened up by different majors is poor quality – at best, it tells you how well people who studied that major years ago have done, but the labor market has probably changed substantially over time. What students really want is forecasts of future returns to different colleges and majors, but this is very difficult! And many people are not even aware of the backwards-looking data. The situation isn’t improved by professors, who generally lack experience outside academia, and sometimes simply lie! I remember being told by a philosophy professor that philosophers were highly in demand due to the “transferable thinking skills” – despite the total lack of evidence for such an effect. Human Capital Contracts would largely solve this problem.

TIPs markets provide a forecast of future inflation. Population-linked bonds would provide similar forecasts of future population growth. Similarly, Human Capital Contracts could provide forecasts of the future returns to future degrees. Lenders would expect higher returns to some colleges and majors (Stanford Computer Science vs No-Name Communications Studies), and so would be willing to accept lower income shares for people who chose those majors. As such, being offered financing for a small percentage would indicate that the market expected this to be a profitable degree. Being offered financing only for a large percentage would be a sign that the degree would not be very profitable. Some people would still want to do it for love rather than money, but many would not – saving them from spending four years and a lot of money on a decision they’d subsequently regret.

What could make clearer the difference in expected outcomes than being offered the choice between Engineering for 1% or Fine Art for 3%?

Certainly I think I would have benefited from having this information available. Most people probably know that Computer Science pays better than English Literature, but that’s probably not a pair many people are choosing from. I was considering between Physics, Math, Economics or History for my major. I knew that History would probably pay less, but didn’t have a strong view on the relative earnings of the others. I probably would have guessed that math beat physics, for example, but in retrospect I think physics probably actually beats math.

Astute readers might object here that I am conflating the benefits of the type of financing (debt vs equity) with the mechanism for pricing the financing (free market or price fixed). If there was a free market in debt financing, lenders could charge different interest rates, and these would provide information to the students. This is true, except that 1) the interest rate would only tell you about the risk you’d end up super-poor, rather than providing information about the full distribution of outcomes, and 2) as student loans cannot be discharged through bankruptcy, there’s not really much reason for lenders to differentiate between candidates. If student loans could be discharged through bankruptcy, the interest rates charged would be informative but also probably very high. Perhaps this would be a good thing!

Education Funding – some illustrative examples.

Because it can be hard to think about these things in the abstract, I’ve tried to produce some worked-out examples. Suppose someone borrows $100,000, and then starts out earning $50,000 when they graduate. Their income grows over time, as they gain experience (maturity) and the economy grows (NGDP/capita). If we assume a 6% return for investors and a 20 year duration, they would have to give up just over 5% of their income of this time period. The repayments would be much more manageable – in year one, it would represent just 5% of their income, as opposed to 17% if they used debt.

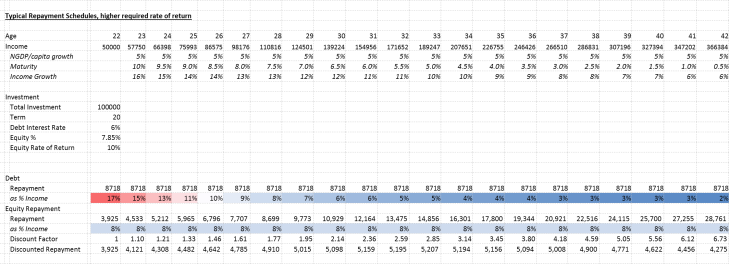

Now, investors might demand a higher rate of return for equity investments, as they’re riskier than debt ( but then again maybe not . Here’s the same calculations, but assuming equity investors require a 10% return vs 6% on debt:

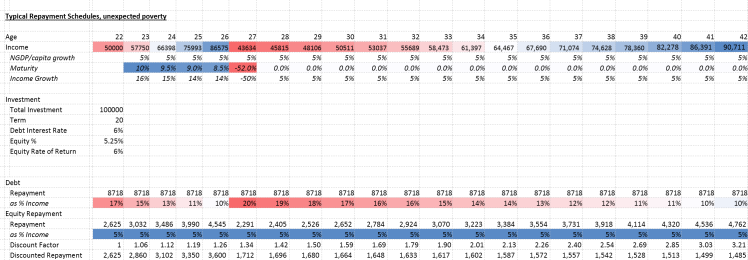

What happens if the student runs into financial difficulty later in life? Here’s what happens if their income falls by 50% and never really recovers:

with equity, the hit is affordable, but with debt they have to pay 20% of their income in debt repayments – perhaps at the same time as having medical problems.

And what about the information value? Well, the investors would be willing to offer them $100,000 for just a 5.6% share, instead of 7.85%, if they took a major that would offer a $70,000 starting salary instead.

I hoped you enjoyed these tables. They are probably the closest you will ever get to a picture on this blog. I did add color to some of them though!

Mentors – Incentive Alignment

The modern world is very complicated, and we can’t expect people to understand all of it. Which is fine, except when it comes to understanding contracts, or credit cards, or multi-level-marketing schemes. At times the complexity of the modern world allows people to be taken advantage of, even in transactions which would be perfectly legitimate had the participants been better informed.

Equity investments have the potential to help a lot here. All of a sudden I have a third party who is genuinely concerned with maximizing my income. I could ask them for advise about looking for a job. Perhaps they could negotiate a raise for me. Indeed, they might even line up new jobs for me! Obviously their incentives are not totally aligned with me. Except insomuch-as happy workers are more productive, they might not put much weight on how pleasant the job is. But true incentive alignment is rare in general; even your parents or your spouse’s incentives aren’t perfectly aligned, and the government’s certainly aren’t. Even better, it’s very clear exactly how and to what degree my inventor’s incentives are aligned with mine: I don’t need to try and work out their angle. I can trust them on monetary affairs, and ignore their advice (if they offered any) with regards hobbies or friendships or whatever else.

Indeed, you could imagine schools that funded themselves entirely through equity investments in their students, and advertised this as a strength: their incentives are well aligned with their students. They would teach only the most useful skills, as efficiently as possible, and actively support your future career progression. This is basically the model App Academy uses:

App Academy is as low-risk as we can make it.

App Academy does not charge any tuition. Instead, you pay us a placement fee only if you find a job as a developer after the program. In that case, the fee is 18% of your first year salary, payable over the first 6 months after you start working.

Compare this to current universities, which actively push minority students out of STEM majors to maintain graduation rates.

Progressive

A clear implication of equity financing is that people who go on to earn more for ex ante unpredictable reasons will pay more than those who are ex post unlucky. As such, this system is mildly redistributive in a manner many people find attractive – like a sort of idealized social insurance that Luck Egalitarians like talking about. The lucky rich pay more and the unlucky poor pay less. Even better, it manages to do so in a voluntary way.

Taxation

The idea of human capital contracts may sound very strange. But we actually already have something similar in taxation. Governments invest in the education, health etc. of their citizens, and then levy taxes upon them. These taxes tend to be proportional to one’s ability to pay; they are some fraction of income, or expenditures (sales taxes). So Human Capital Contracts should feel familiar to socialists and the like.

There are of course a few differences between Human Capital Contracts and taxation. For example,

- Human Capital Contracts are optional, whereas taxation is mandatory.

- Human Capital Contracts give you more choice about what you spend the money on, whereas governments typically give you little choice.

- Finally, Human Capital Contracts are customizable; you could negotiate different terms with the lender (like the % share you’re selling, or the income level at which you start repaying, or the timing of repayments), whereas individuals rarely get much choice about the taxes they will be made to pay.

Indeed, the advantages of human capital contracts suggest a new way of doing taxation: the state could simply claim a certain % ownership of its citizens. Perhaps it might demand a higher % for those who use public education or public healthcare.

The idea of the state literally owning (a stake in) its citizens, without their consent, might sound evil. But this is basically what the government already does with taxation – it claims a certain fraction of your income, leaving you no recourse. Even renouncing your citizenship will not persuade the IRS to let its property go. Human Capital Contracts just make it more explicit that the governments of most countries effectively own somewhere between 30% – 60% of their populations. Worse, if they want to they can increase their ownership stake without the consent of those affected. Compared to this, it is hard to make voluntary Human Capital Contracts sound problematic.

However, this suggests a danger with equity investments in people. At the moment you can escape most governments by fleeing abroad. The couple of exceptions are largely viewed as immoral aberrations, not the rightful state of affairs. This exit-right provides a vital check on their power, and forces them to compete to some degree. Without it they can descend to the most abusive tyranny. If equity investments became widely recognized, however, governments might start to recognize each other’s ownership of its population to a greater degree than now, which would make them harder to escape. Of course, virtually any innovation can be opposed by pointing out they make it easier for governments to oppress ‘their’ populace, from coinage to maps to cell phones. Perhaps a more powerful government would be a more benign one, as many different people have argued – though perhaps not.

Mechanics

Operationally this would be slightly more complicated than taking out a standard loan, because the amount owed to the lender would be variable. As such, they need to verify my income so they can check I’m repaying the correct amount. There are many ways this could be done, but an obvious one would be through the tax system; I would submit to the lender a copy of my tax return to show my annual income. Perhaps this could be automated through TurboTax. An even easier option would be if the payments were deducted from my paychecks – this is how English student loans work.

Possible Regulations

One option for regulating the system would be to impose a maximum amount of equity an individual could sell. This would prevent people from selling 100% of themselves, which might be a bad idea! Though for-profit investors would probably be uninterested in buying up to 100%, as the individual would lack any reason to actually work. Probably the only people interested in buying 100% ownership would be cults, communist co-ops and terrorist movements.

Another would be to regulate the contingencies that could be attached to such contracts.

A third would be to prohibit the investor from employing the investee, or vice versa.

Adverse Selection

One of the biggest impediments to such a system might be adverse selection. Students have ‘insider information’ about their future prospects – they know about their career plans. The less you expect to earn, the more attractive selling equity is over the fixed payments of debt. Conversely, the more you expect to earn, the less attractive equity is vs debt. As such, the students who opted for equity financing might be disproportionately the students with the lowest expected outcomes. This would increase the % investors would demand in return for funding, further deterring the higher-expectation students, until eventually only the very lowest-expectation students would remain in the pool.

We could imagine this being a big issue in some subjects, like physics, where there is a large variance in income for the different exit routes – grad school vs industry vs quant finance. For others it’s less of an issue; if you go to law school you’re probably aiming to become a lawyer, though even there you might choose between criminal or corporate law.

However, there are several factors which would mitigate against such an outcome. Firstly, the risk aversion we discussed earlier means students would probably be willing to pay a substantial amount to avoid the risk associated with debt. Adverse selection would mean it would be even more attractive to students pessimistic about their long-term earnings, but so long as it is attractive enough for the optimistic ones, it would still work.

Indeed, this is basically how it works for health insurance. In theory adverse selection is a problem for private health insurance; but in practice there is not much evidence this is actually a problem; healthy people still buy health insurance.

The effect would also be substantially reduced by students own lack of knowledge about their futures. Many students change their mind over the course of their studies about what they want to go on to do. So some low-expectation students might take out equity financing, thinking they were being cunning… and then change to a high paying career track! This seems to be the more common direction of travel in general; students go to college planning on becoming human rights lawyers, or engineers, or artists, but instead end up as corporate lawyers, investment bankers and advertisers.

So this is a problem I’d expect the bond/equity/insurance market to be more than capable of dealing with.

Addendum: Speculative Extensions

Here are some more ideas where equity investments in people could be useful. The idea could still be valuable even without these though; education is probably the best use-case.

Parents

Once upon a time the land was rich and fruitful, and the people were fecund with beautiful offspring.

… maybe that never happened, but fertility rates definitely have fallen over time, probably to our detriment. Future people matter, a lot! And even if they didn’t, we still need someone to fund social security.

One guess as to why fertility has dropped is once upon a time your children could be relied upon to live near you, following your customs, and supporting you in your old age, though its unclear if this ever made strictly economic sense. Now, however, children feel much less moved by filial piety, and frequently move far away. As such, parents seem much less value in having children, and only do so out of charity – raising a child takes a lot of effort, and the modern world is full of super-stimuli to distract you from productive procreation. Giving parents a small equity stake in their children would go some way towards recognizing the investment parents put into their children, and hopefully boost fertility rates.

It would also encourage parents to support their children and their careers; now the high-flying child is not merely a source of pride but also a source of retirement. A friend I discussed this with suggested that first-generation immigrants tended to give their children very practical advice about school, careers and relationships, whereas whites tend to be more wishy-washy; perhaps this would promote a return to reality-based parenting.

Divorce settlement

Another niche case where these could be useful would be divorce settlements. The classic feminist argument about divorce settlements was that the woman had invested in domestic and family labor, which was disrupted by the divorce, while the man had invested in his career, which he kept. Partly as a result of arguments like this, we now see divorce settlements where one party gets a claim to some of the resources of the other.

However, a fixed sum is not a very natural way of dealing with this. The woman, in entering marriage, assumed she would be benefiting from a certain share of the man’s output. If he were successful, this would be more; if he came upon poor fortune, this would be less – rather than taking a costly and messy court case to adjust the payments. Human Capital Contracts would allow a divorce settlement to recognize this: in a divorce were the man were at fault, the woman might be granted a 1% equity share for each year of marriage.

Obviously if you thought permitting divorce was a mistake – “til death do us part” – then you’d have little interest in this application.

Further Reading

Further Reading: Risk-Based Student Loans