There are a few pieces of information that are required to properly analyze the value of Giving What We Can‘s membership.

They’re necessary for GWWC’s managers to evaluate different strategies. If GWWC was an object-level charity, we wouldn’t donate to it without knowing these numbers. And if GWWC were a public company, investors would not provide funding without such disclosure. As such, hopefully these metrics are already being collected internally, and publicly sharing them should not be very difficult, though very valuable. If not, GWWC should start collecting them!

GWWC already publishes the number of members it has at any given point and the total amount pledged. From this it’s easy to derive how many joined in any given year. However, it’s hard to judge what these people did later – how many fulfilled the pledge, and how much did they donate? Worse, this makes it hard to forecast the value of a new member, so we can’t tell how much effort we should put into extensive growth. As far as I can see (sorry if I just couldn’t find the data), we do not currently release the data required to make this analysis.

As part of it’s annual report, GWWC should release data on each cohort: how many of that cohort fulfilled the pledge by donating 10%; how many were ‘excused’ from donating 10% ( e.g. by being students); how many failed to abide by the pledge, donating less than 10% despite having an income; and how many did not respond.

Example Disclosure

In case it’s confusing what exactly I’m suggesting GWWC release, here’s an example (with totally made-up numbers). As part of it’s 2014 annual report, GWWC could report:

- 2011 cohort:

- Of the 107 who joined in 2011…

- 75 donated over 10% in 2014

- 15 were students and did not donate 10% in 2014

- 10 had incomes but did not donate 10% in 2014

- 7 could not be contacted in 2014

- Total of $450,000 donated in 2014

- 2012 cohort:

- Of the 107 who joined in 2012…

- 50 donated over 10% in 2014

- 53 were students and did not donate 10% in 2014

- 2 had incomes but did not donate 10% in 2014

- 2 could not be contacted in 2014

- Total of $300,000 donated in 2014

- 2013 cohort:

- etc.

While in the 2013 annual report, GWWC would have reported

- 2011 cohort:

- Of the 107 who joined in 2011…

- 45 donated over 10% in 2013

- 56 were students and did not donate 10% in 2013

- 3 had incomes but did not donate 10% in 2013

- 3 could not be contacted in 2013

- Total of $250,000 donated in 2013

- 2012 cohort:

- Of the 107 who joined in 2012…

- 16 donated over 10% in 2013

- 89 were students and did not donate 10% in 2013

- 1 had incomes but did not donate 10% in 2013

- 1 could not be contacted in 2013

- Total of $100,000 donated in 2013

This would allow us to see how each cohort matures of time, answering some very important questions:

- How much is a member worth, after taking into account the risk of non-fulfillment?

- How much does the value of a member differ with the discount rate we use?

- How does the donation profile of a member change over time – does it rise as they progress in their career or fall as members drop out?

- Are the cohorts improving or deteriorating in quality? Are the members who joined in 2012 more likely to still be a member in good standing in 2014 than they 2010 cohort were in 2012? Do they donate more or less?

There are some other numbers that might be nice to know, for example breaking the data down by age, sex, nationality, or even CEA employee vs non-employee, but it’s important not to impose too high a reporting burden.

Why this is not idle speculation

This might seem a bit ambitious. Yes, it would be nice if GWWC released this data. But is it really a pressing issue?

I think it is.

Bank problems: Extend and Pretend

Sometimes banks will make a series of bad loans – loans which are repaid at a significantly lower than expected rate, perhaps because the bank was trying to grow aggressively. When the first signs of this emerge, like people being late on payments, banks have two alternatives. The honest one is to admit there is a problem and ‘write down’ the loan – take a loss to profits. The perhaps less honest one is to extend and pretend – give the borrowers more time to repay and pretend to yourself/auditors/investors that they will come good in the end. This doesn’t actually create any value; it just delays the day of reckoning. Worse, it propagates bad information in the meantime, causing people to make bad decisions.

Unfortunately they neglected the Litany of Gendlin:

What is true is already so.

Owning up to it doesn’t make it worse.

Not being open about it doesn’t make it go away.

And because it’s true, it is what is there to be interacted with.

Anything untrue isn’t there to be lived.

People can stand what is true,

for they are already enduring it.

—Eugene Gendlin

GWWC: Dilutive Growth?

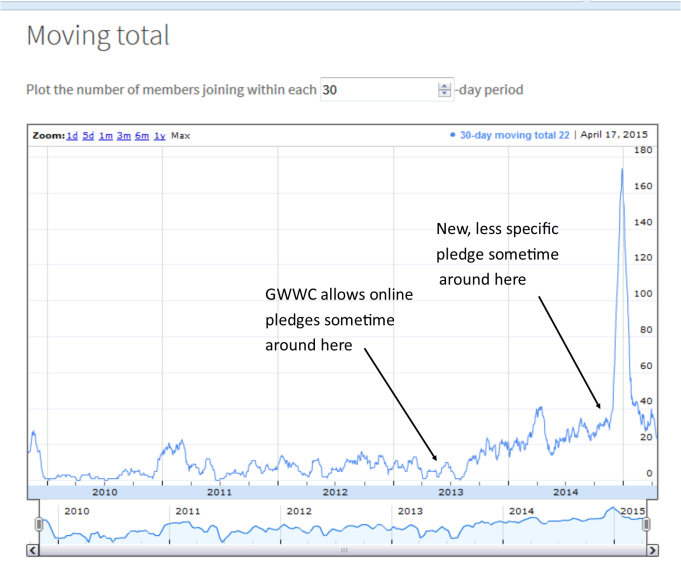

About a year ago, people were concerned that GWWC’s growth was slowing – only growing linearly, rather than exponentially. This would be pretty bad, and people were justifiably concerned. However, GWWC made a few changes with the aim of promoting growth. Most pertinently:

- Allowing people to sign up online, rather than having to mail in a hand-signed paper form. This happened between April and June 2013.

- Adjusting the pledge to become more cause-neutral, rather than just about global poverty. This happened late 2014.

The latter change was somewhat controversial, but I didn’t see much discussion of the former at the time.

The concern is that, though these measures have increased the number of members, they may have done so by reducing the average quality of members. Making it easier to join means more marginal people, with less attachment to the idea, can join. This is still good if their membership adds value, but they dilute the membership, which means we shouldn’t account for the average new member being signed up now as being equally valuable as the members who joined up in 2010. Additionally, the reduction in pomp and circumstance might reduce the gravitas of the pledge, making people take it less seriously and increase drop-out rates. If so, moving to paperless pledges might have reduced the value of sub-marginal members as well as diluting them.

The comparison with banks should be pretty clear – a bank that’s struggling to grow starts accepting less creditworthy applicants so it can keep putting up good short term numbers, but at the cost of reducing the long-run profitability. Similarly GWWC, struggling to grow, starts accepting lower quality members so it can keep putting up good short term numbers, but at the cost of reducing the long-run donations. This makes it harder to forecast the value of members, and might lead to over-investment in acquiring new ones.

This seems potentially a big risk, and it’s the sort of issue that this data would allow us to address. Of course, there are many other applications of the data as well.

And GWWC in fact has even stronger reasons than banks to report this data. The bank might be wary of giving information to its competitors, but GWWC has no such concerns. Indeed, if releasing more data makes it easier for someone else to launch a competing, better version of GWWC, all the better!

If you liked this you might also like: Happy 5th Birthday, Giving What We Can and GiveWell is not an Index Fund